Exploring the role of gene splicing in triple negative breast cancer

Research Highlight | December 3, 2019

They looked at cells from breast cancers and found that only a few splicing factors seemed connected to the cell’s cancerous behavior. In particular, three splicing factors gave the cells the same wrong recipe, enhancing the cell’s ability to grow and to migrate. Among these, a splicing factor called TRA2B seemed particularly enriched in triple-negative breast cancers. Triple negatives are the worst breast cancers: they have the highest rates of metastasis, worst prognosis, and no targeted treatments.

The researchers blocked TRA2B expression in cells, in tiny tumors in a petri dish, and in mice. In all three situations, cells lacking TRA2B were unable to metastasize.

Identifying TRA2B was exciting. Finding a way to block it could provide a treatment for this most dreaded form of breast cancer. The researchers hope to learn more about how the splicing factors become dysregulated and eventually develop a drug to target them.

Targeting splicing defects has become a reality with the approval of Spinraza, a first of its kind drug that corrects abnormal splicing. Spinraza was developed by Professor Adrian Krainer, a molecular biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and co-author on this study, and is the first FDA-approved drug to treat children with spinal muscular atrophy. Researchers hope that in the future this type of drug can be used to treat other diseases with splicing defects, including cancer.

“Once we know that a splicing factor is upregulated and promotes disease, a targeted treatment could involve a selective inhibitor of that factor, or restoring the correct editing of one or more of its crucial targets,” says Krainer.

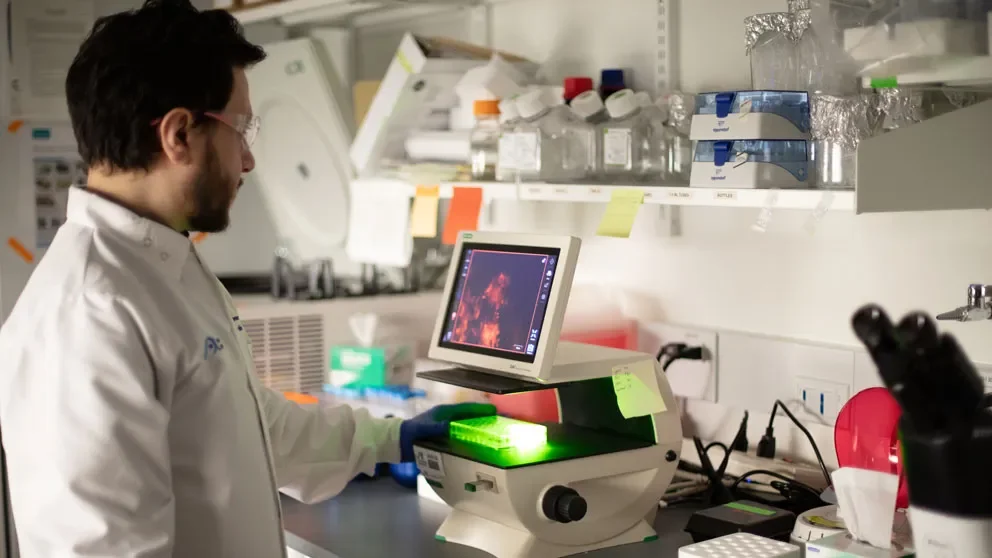

The research team worked with Martin Akerman at Envisagenics, and it used SpliceCore, the company’s cloud-based software platform for splicing analysis to identify downstream targets of TRA2B that are critical for its tumor promoting function and could be novel therapeutic targets.

mouse-model-paved-the-way-for-sma-drug

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of General Medical Sciences at the National Institutes of Health, the Susan G. Komen Foundation for the Cure, the Terri Brodeur Breast Cancer Foundation, and JAX start-up funds.