JAX researchers reflect on why they chose careers in science and explain what keeps them coming back to the lab every day.

Beth Dumont, Ph.D., assistant professor

I am descended from early pioneers of computer technology, Maine outdoorsmen, and women who’ve challenged stereotypical gender roles. I’m a product of my environment: a female scientist who uses computational approaches to understand genetic variation in the natural world.

In the course of a typical day, I make new discoveries, script computer code, carry out statistical analyses, manipulate cells and DNA, teach, see things too small to be observed by the naked eye, ask questions, read about the latest scientific advances, write, and learn.

I’d be bored in any other career.Every day I get to study the natural phenomena that I find most fascinating. No other career affords that kind of intellectual flexibility, targeted mental focus, or built-in insurance for job satisfaction.

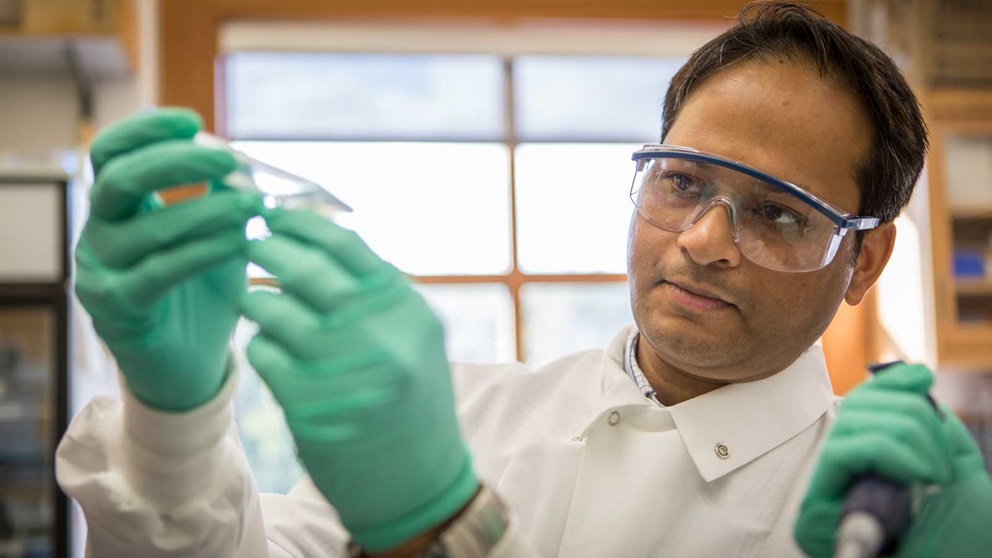

Vivek Kumar, Ph.D., assistant professor

I'm keen on finding genes and pathways that lead to behavioral disorders, and ultimately figuring out whether we can correct those genes and pathways to lead to therapy and pharmacological interventions. We're doing pretty cool stuff — we do everything from molecular genetics to using computational and machine learning tools. I look for areas that I feel are not well understood at the molecular level. In the area where I am now, I feel like we know a lot but certain tools haven't been applied.

I've said this to all my students, and I’ll say it to anyone who will listen: science is a lot about how you handle failure. Think about a good scientific experiment: you have a question you want to ask, and you may try 5 or 6 times before you find the right technique or get results. Then you move on to the next experiment, which may take another half dozen times to perfect. It's all about how you take those failed experiments — the ones that don't get you the data you want — and learn from that. I like learning. People who can't handle failure have a tough time in science.

I'm like a dog with a bone — if I have a problem, I’ll work really hard to solve it. My nightmare job would be doing something that is the same day in and day out. In my lab every day I’m doing new things, cool things.

Catherine Kaczorowski, Ph.D., assistant professor

To me, extending lifespan without extending cognitive longevity is extending years of your life where you would be really, really unhappy. Even if you were free from cardiovascular disease and cancer, your mind wouldn't keep up with the health of your body. In order to avoid that outcome, I focus on how the brain is aging and how information storage and recall is altered by the aging process.

In the context of disease, you see people who are in their 40's, 50's and 60's unable to perform normal activities like getting around and remembering who their loved ones are. The idea of people not knowing where they are or who they're surrounded by and feeling like they were captives is truly terrifying. I think that's where aging and Alzheimer's disease came in for me: that idea of people suffering within their bodies and not being able to understand what's going on around them.

Earlier in my career, I would have said it was just about curiosity and trying to solve problems. I like to do things that are really challenging. I think the way that the brain encodes and stores information and sort of the mysteries of the brain are interesting. But now that I am a faculty member, and I've gone and given talks to caregivers and patients and people in the community, I think a lot of my focus has shifted to impact. You can't meet people who are suffering and not have that affect you. I definitely think that now I'm much more mindful of why I'm trying to solve the problem.

Alex Fine, predoctoral student

I work with Associate Professor Greg Carter’s computational group, working on gene networks. I’m really interested in data integration, taking different data types (mostly genomic) and figuring out how to integrate them into a more thoughtful single model.

I'm passionate about the communication side of computational work. I like translating complex questions into models that wet bench biologists can learn from. I can take massive data sets that most biologists don't know how to look at and learn something from, run analyses, and spit out a figure, and the wet bench biologist will have learned something. It’s about going from data to information.

I try to volunteer every year at Camp Sunshine, which is a camp for children and families facing life-threatening illnesses. In non-clinical research, you don't often get to see the people that you're helping. For some people that's nice because it would be hard, but as someone who does not get to see the direct output of what I’m doing, it's nice to get a reminder of why we do this.

Ambreen Sayed, predoctoral student

I'm a very curious individual by nature. I always have a dozen questions for every answer, and I think that's the basis of what drives any scientist. You have to have this innate curiosity about why things happen. Every time I find something or learn something new, I have a lot more questions, and that keeps the cycle going. I come back to the lab to answer my questions.

On a daily basis, it's not like I learn something new every single day. It's the long term goal that I'm pursuing. I have to constantly be thinking about the bigger picture. I'm testing for cognitive impairments in a model of muscular dystrophy that's very rare and affects very few people, but when it does, it affects at birth, so you have these babies living a very low-quality life. They can't walk, they can't talk, and they have severe cognitive disabilities. So that incentive, that I'm going to eventually find something that helps them, is what keeps me going in the long run.

Kristen O'Connell, Ph.D., assistant professor

I was always really good at science; those were always the classes in school that were easiest for me and that I liked. When I would read, I’d choose to read about science. I have no artistic ability whatsoever, which helped keep me focused on science. I was raised by my grandmother, and she really encouraged those interests. She’d buy me books of experiments that we’d do together at home.

This is the best job in the world. This isn't really a job. It's not that different from the experiments with baking soda and vinegar that I used to do when I was six. The toys are bigger and more expensive, but you're still trying to figure things out. I can't believe I get paid to do this. I'm doing the thing I’m good at that I really like to do.

Greg Cox, Ph.D., associate professor

I love cars. I’m kind of an auto mechanic, always working on a car. I love figuring out how things work. I love taking things apart, fixing them, and putting things back together. Genetics is kind of that way: once you understand how it works, you can change things around.

Science is about tinkering with things to understand how they work, but it’s not quite like looking at cars, where there is a manual. We have the underlying basis with the genome, but there are no real instructions. Things get complicated very quickly when you try to find out how and where all those genes are expressed. We're always figuring out mechanisms, discovering new functions.

It's really about discovery — you’re always learning something that nobody else in the world knows. Being the first person to know or see something is exciting and kind of addictive.

Lucie Hutchins, software engineer

I always wanted to do bioinformatics. I love biology and I love computation, and I wanted to work in a field that uses both.

Biology came first. I grew up from an early age thinking I was going to become a doctor. I always liked the science. I did not discover computation until I was in college here in the United States. I started looking into job opportunities, saying “what if I don't get into med school?” I started looking at the areas where companies were looking, and I saw computer science and I was like "wow, this is great." It seemed like kind of a mystery.

I'm a problem solver — I like challenges. I have that mentality, that mindset. There are so many problems in research, and I think we need more problem solvers to create solutions. I know that in that field I will always be busy trying to come up with something new, doing something interesting. I know that there are so many things that still need to be done. Computational people with a biology background can definitely be very handy to connect the dots.

Kevin Johnson, Ph.D., postdoctoral associate

Toward the end of my PhD, an opportunity arose to study a recently discovered DNA modification, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, which I discovered is an important marker in aggressive brain tumors. This project got me excited about brain tumor biology.

I believe the project I'm working on will yield unprecedented knowledge about the evolutionary course of individual cells within a brain tumor, and provide insight into potential treatment options for cancer patients.

What I like most about having a career in science is that you get paid to learn. You get paid to teach yourself. Your vocation is to learn and help others learn about the world. If you enjoy being a student and a life-long learner, becoming a scientist is a great option. You continually push your knowledge boundaries, and I have found great meaning in testing new hypotheses.

Cat Lutz, Ph.D., senior research scientist

I think I'm a good scientist; I don't think I'm a great scientist. I think I'm a good business person; I don't think I'm a great business person. I'm also interested in the legal side of things. What I like best is that I've been given the opportunity to do all of those things, and I've been pretty successful in blending it together.

During my first laboratory internship in college, it was fun having exposure to the camaraderie and having insight into what these folks actually do. It made me curious. When I came to JAX, I got hooked even more — you can't avoid it. Each new mouse model is like a little mystery packaged up — there's something different about the mouse, and we have to figure out why.

Photos by Sarah Sullivan and Tiffany Laufer