Aging is complex. It’s more than the number of candles on a birthday cake.

Just think about your closest friends — some will see their first gray hair in their 20s, others seem baby‑faced well into their 40s. Every person ages at a different rate, and that’s the difference between what scientists call chronological aging and biological aging. And just like no two people age the same way, aging affects breast cancer risk in ways we’re only just beginning to understand.

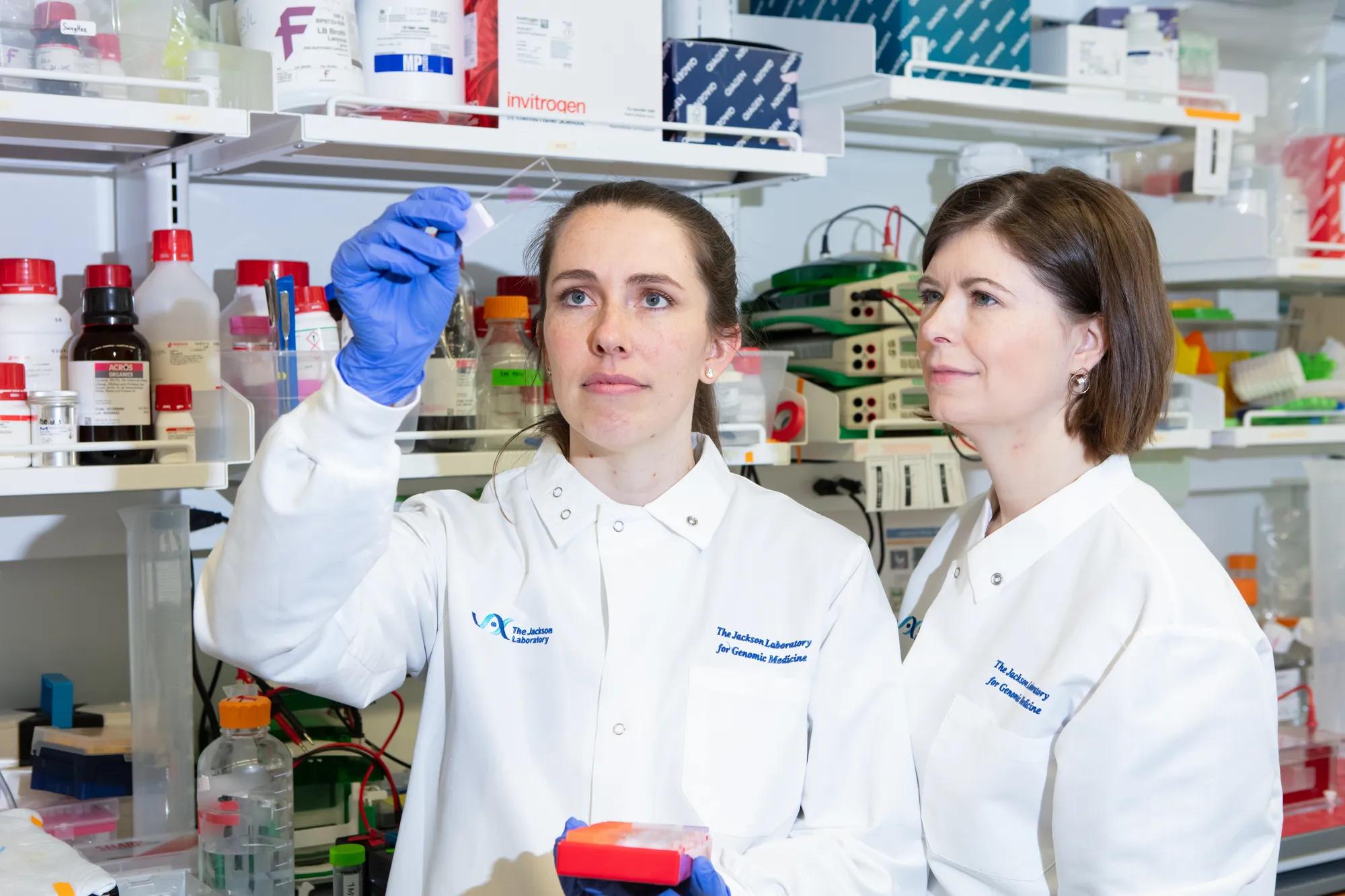

Statistically, one in eight women will develop breast cancer in their lives and 80 percent of all breast cancers occur in women over 50. Researchers in the Anczuków lab at The Jackson Laboratory are focused on understanding the how and the why.

How does the breast tissue change as women age and why do those changes increase the risk of breast cancer?

Understanding aging breast tissue

Breast tissue isn’t a monolith. It’s made of several different types of specialized cells including epithelial cells, which line the milk ducts; fibroblasts, which help form connective tissue; immune cells that fight infections; adipocytes or fat cells; and, stromal cells that help form organs. As people (and their cells) age, those cells have a harder time doing their job.

“We lack an understanding of how breast tissue changes at the cellular and molecular level, and how that could lead to cancer,” says Olga Anczuków, associate professor at JAX and co-program leader of the JAX Cancer Center. Breast cancer has been a focus of her lab’s research for years.

There is a need to understand why we’re more likely to develop breast cancer with age, and if we can do anything to delay that, detect it early, or prevent it altogether,” says Anczuków.

The external signs of aging are obvious — gray hair, laugh lines, stiff joints. But at the cellular level, aging leads to molecular changes that are harder to see.

Whereas you might wake up with a new forehead wrinkle, your cells see errors at the molecular level. In younger tissues, the cells that make up breast tissue are very good at doing what they’re meant to do (something called “specialization”), but over time, the cells that make up tissues can lose function.

“With age, specialized cells in the breast kind of stop doing their jobs, they lose a bit of that specialization and start behaving differently. That may lead to a tissue that doesn’t function properly and is more prone to cancer,” says Brittany Angarola, associate research scientist in the Anczuków lab.

Drawing a map of aging impacts

In a paper published earlier this year in Nature Aging, Anczuków, Angarola and colleagues created an atlas that revealed key cellular and molecular changes that breast tissue undergoes during aging. The paper was a transdisciplinary collaboration with the Ucar, Korstanje, Chuang and Palucka labs at JAX. The researchers compared genetically identical young female mice to older mice and discovered changes in both the cells and the molecular components of the cells with age.

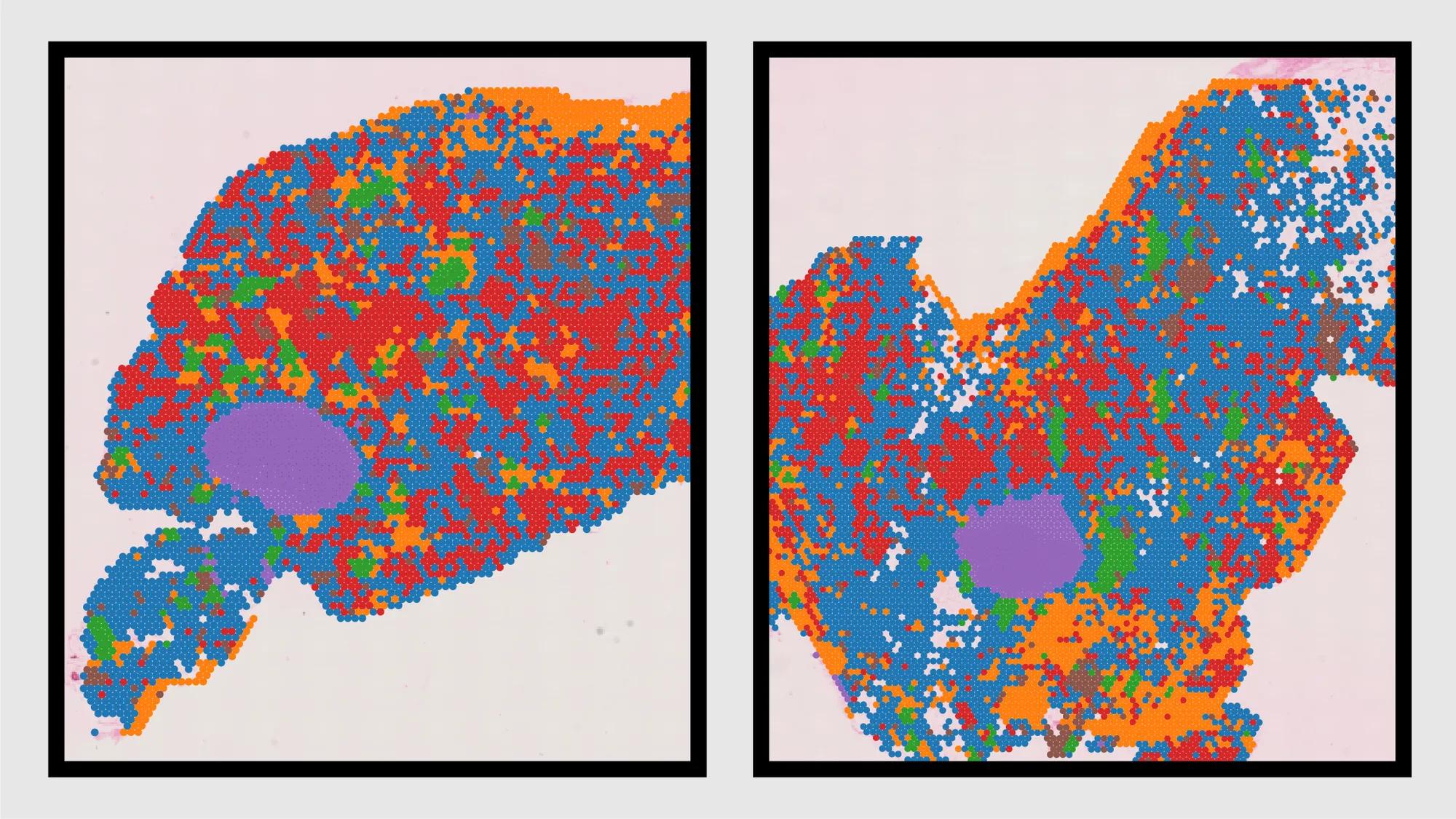

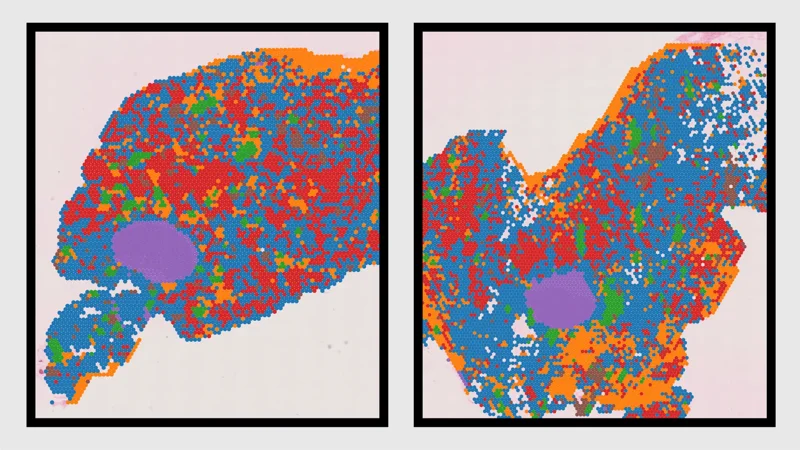

To create this atlas, the team utilized cutting-edge single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies to map molecular changes in breast tissue. Single cell sequencing captures data from individual cells, rather than averaging measurements across a population of cells.

Spatial transcriptomics allows them to add geo-localization tags and map within a tissue — in this case, the mammary glands of mice where a specific gene is expressed. This allows the researchers to identify exactly which genes are expressed within a tissue sample, giving insights into the cellular activity and cellular interactions based on the location within the tissue.

“This technology can offer the positional information of each RNA molecule, and give us insights into the cellular activity and cellular interactions based on the location within the tissue,” says Hyeon Gu Kang, postdoctoral researcher in the Anczuków lab, and co-author of the study.

Transcriptomic changes reflect the activity level of genes in a cell, highlighting which genes are “turned on” or “turned off.” This provides crucial insights into how a cell functions, responds to stimuli and contributes to disease states like cancer.

“For the first time, we connected changes at the epigenetic and the transcriptomic levels during breast aging,” says Anczuków. “Epigenetic changes are a hallmark of aging, and lead to a gradual decline in tissue and cell function. Our work mechanistically links these two key molecular processes in breast aging.”

Creating an early- detection system

To see if these age-related molecular changes in mice were reflected in human breast cancer risk, the team compared their data to publicly-available transcriptomic data from human breast cancer tumors. They found that a subset of the age-related molecular signatures in mice mirror patterns seen in human breast cancers — suggesting that the aging breast cells and their microenvironment play a direct role in cancer risk and can provide valuable warning signs.

“Finding these overlapping pathways was really exciting,” says Angarola. “It suggests that aging-related shifts in healthy tissue might create a more cancer-friendly environment before tumors even form.”

The breast tissue cell atlas they created is open-access, offering a critical tool for the broader cancer and aging research communities to explore how aging influences cancer risk.

Early detection and early treatment have been incredibly impactful in battling cancer,” says Angarola, “and we are striving to keep moving the needle in breast cancer prevention and therapy.”

The team hopes that one day it will be possible to refine these molecular signatures into a set of biomarkers that could turn a routine blood test into an early warning system, allowing doctors to detect signs of breast cancer before a tumor appears.

“Our research leverages the unique intellectual and technical resources of the JAX Cancer Center, which has a goal to uncover the molecular mechanisms that drive aging-associated dysfunction and their impacts on cancer and cancer therapies,” says Anczuków. “Our work now focuses on understanding the impact of these age-related changes on mammary cells, developing tests to measure these cancer-associated signatures in breast and blood, and creating novel approaches to delay or prevent these changes.”

Philanthropy fuels discovery, helping cancer researchers take the next steps toward earlier detection and prevention. This work was supported by the JAX Cancer Center, the JAX Center for Aging Research, The V Foundation, The Tallen-Kane Foundation, The Scott R. MacKenzie Foundation and The Hevolution Foundation.

Help shape the future of human health. Support JAX today!

This story was featured in Search magazine, Vol. 18, No. 1, published in spring 2025. Search is a publication from The Jackson Laboratory focused on research discoveries and human health.

Learn more

Landmark atlas reveals how aging breast tissue shapes breast cancer risk

JAX researchers have uncovered how age-related cellular and molecular changes may contribute to breast cancer development.

View more

The Anczukow Lab

The Anczukow Lab at The Jackson Laboratory explores the role of alternative RNA splicing in cancer development. Discover groundbreaking research targeting splicing mechanisms to identify novel biomarkers and precision medicine therapies.

View more