Seeing what’s hidden: Using AI to transform pediatric cancer care

Article | September 25, 2025

More than 100 subtypes exist, and symptoms can be vague—pain, swelling, or a lump somewhere in the body. Pinning down the exact type of sarcoma often requires a complicated chain of tests: genetics, protein staining, and, critically, the judgment of pathologists trained to recognize these uncommon tumors.

That expertise can be hard to come by, especially for families who live outside of major metropolitan areas with large medical centers. There’s an international shortage of highly-trained pathologists with sarcoma experience, often leaving families waiting while tissue samples are shipped for review. Even then, specialists sometimes disagree. Diagnoses often vary between experts and valuable time is lost as the cancer progresses. As targeted therapies expand, identifying the correct sarcoma subtype is essential. A misclassification can delay care or prevent patients from receiving the most effective treatment.

Adam Thiesen, an M.D./Ph.D. candidate at UConn Health and The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) in the Chuang lab is working on a different approach. Under surgical oncologist Jill Rubinstein, who is also a senior research scientist in the Chuang Lab, Thiesen is training artificial intelligence to read tumor slides directly, delivering fast, consistent diagnoses that can lead families to better treatments, faster.

“We wanted to see if we could eliminate all of those excess requirements for patients and try to make a diagnosis from an image of the tissue alone. And we’ve done a pretty good job so far,” said Thiesen.

Not your average AI

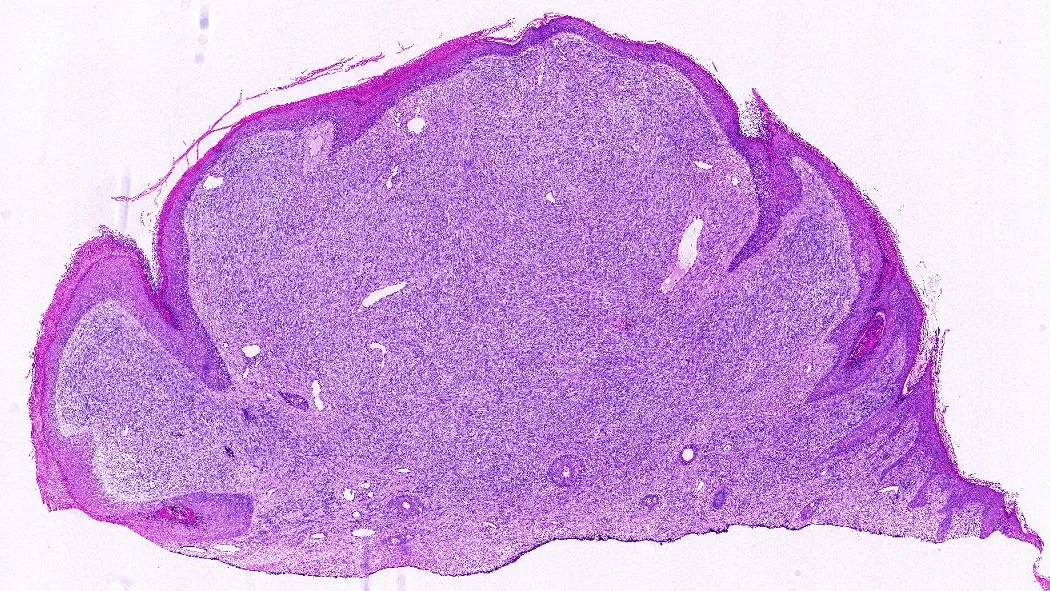

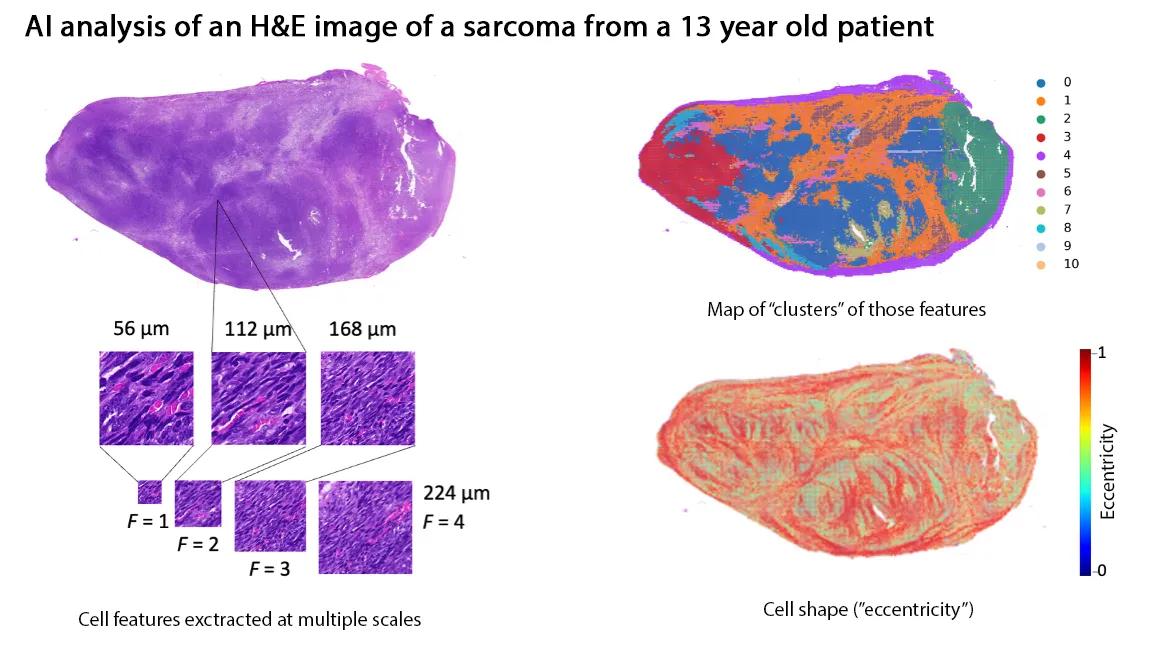

When people think of AI, they often imagine large language models that generate text. Thiesen’s system is different: it analyzes images—specifically, digitized pathology slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Pathologists examine these slides for subtle patterns in cell shape, clustering, and texture. The AI can scan for the same things, at scale, breaking each slide into thousands of tiles, converting them into numerical “fingerprints,” and assembling a prediction of which sarcoma subtype the tumor most resembles.

“By digitizing pathology slides, we turned what a pathologist sees under the microscope into numerical data a computer can analyze,” said Thiesen. “The way your phone recognizes faces in photos, our AI models learn to recognize tumor patterns and classify them into sarcoma subtypes.”

Filling critical gaps

This kind of tool won’t replace experts, but it can extend their reach. In regions without sarcoma specialists, AI could serve as a virtual second opinion, giving doctors and families faster, clearer answers. Even at top cancer centers, models trained on large datasets may catch subtle features that human eyes sometimes miss.

Their system is deliberately lightweight, without the need for high-powered equipment. It was designed for clinicians to run on standard laptops once a slide is digitized. It’s also open source, inviting other groups to contribute images and refine the model.

“These models will only get stronger if pathologists are part of the process,” Theisen said. “They can point out subtle cellular differences—shapes, colors, tiny structural changes—that even advanced AI might miss on its own. By annotating those features, pathologists help train the models to recognize what really matters in the clinic.”

Building momentum

In preliminary data, Thiesen and his collaborators have shown their approach can distinguish between challenging sarcoma subtypes with striking accuracy. The next step is scale: building larger, more diverse datasets to teach the model to recognize even the rarest forms.

For families, the promise is simple: a biopsy taken in a community hospital could soon yield a reliable sarcoma diagnosis in hours or days rather than weeks or months. Faster answers mean faster treatment decisions—and potentially, better outcomes.

Learn more

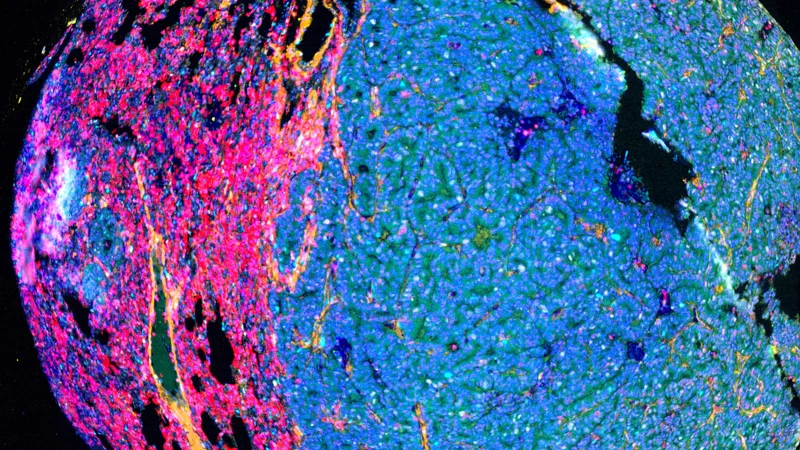

Tissue AI: The future of tumor imaging

Tissue AI is like upgrading from a paper atlas to a high-resolution, interactive GPS system. Traditional imaging methods are like a basic street map—outlining major landmarks but missing the fine details important to how a city truly functions.

View more