Organoids and organs-on-chips bridge the gap between basic biology and human health, offering insights to scientists and more precise diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for patients.

Science in 3D: How organoids and organs-on-chips can help scientists study host-immune-microbiome interactions

Article | September 5, 2025

When scientists want to understand how a disease begins (or how they can stop it), cells grown in a dish are often the first step.

But while those flat, 2D cultures have taught us a lot, they don’t behave the way cells and organs do in the body. The human body is complex and our tissues are three-dimensional, in constant motion, and shaped by the interplay of many different cell types. That’s where technologies like organoids and organs-on-chips come in.

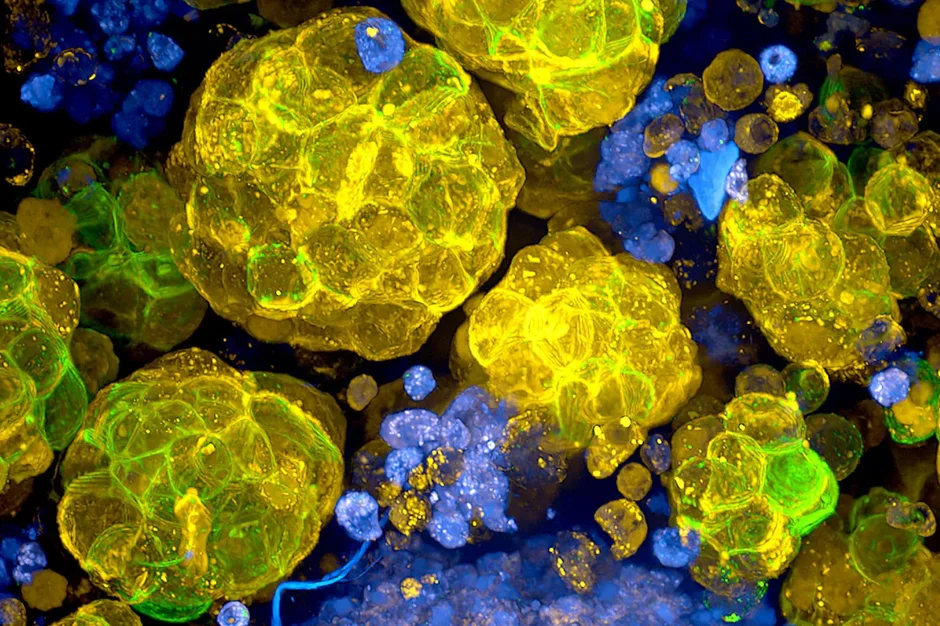

Think of organoids as miniature versions of human tissues and organs. By guiding stem cells, or cells from patient biopsies, researchers can grow tiny 3D structures that mimic parts of the gut, skin, or other organs. For example, JAX scientists can grow tumor organoids from human colon cancers. These small but sophisticated models not only recreate how cancer cells behave in the body, but also provide a platform for drug screening. Using fluorescent markers, researchers can quickly see which treatments kill tumors and which leave them untouched.

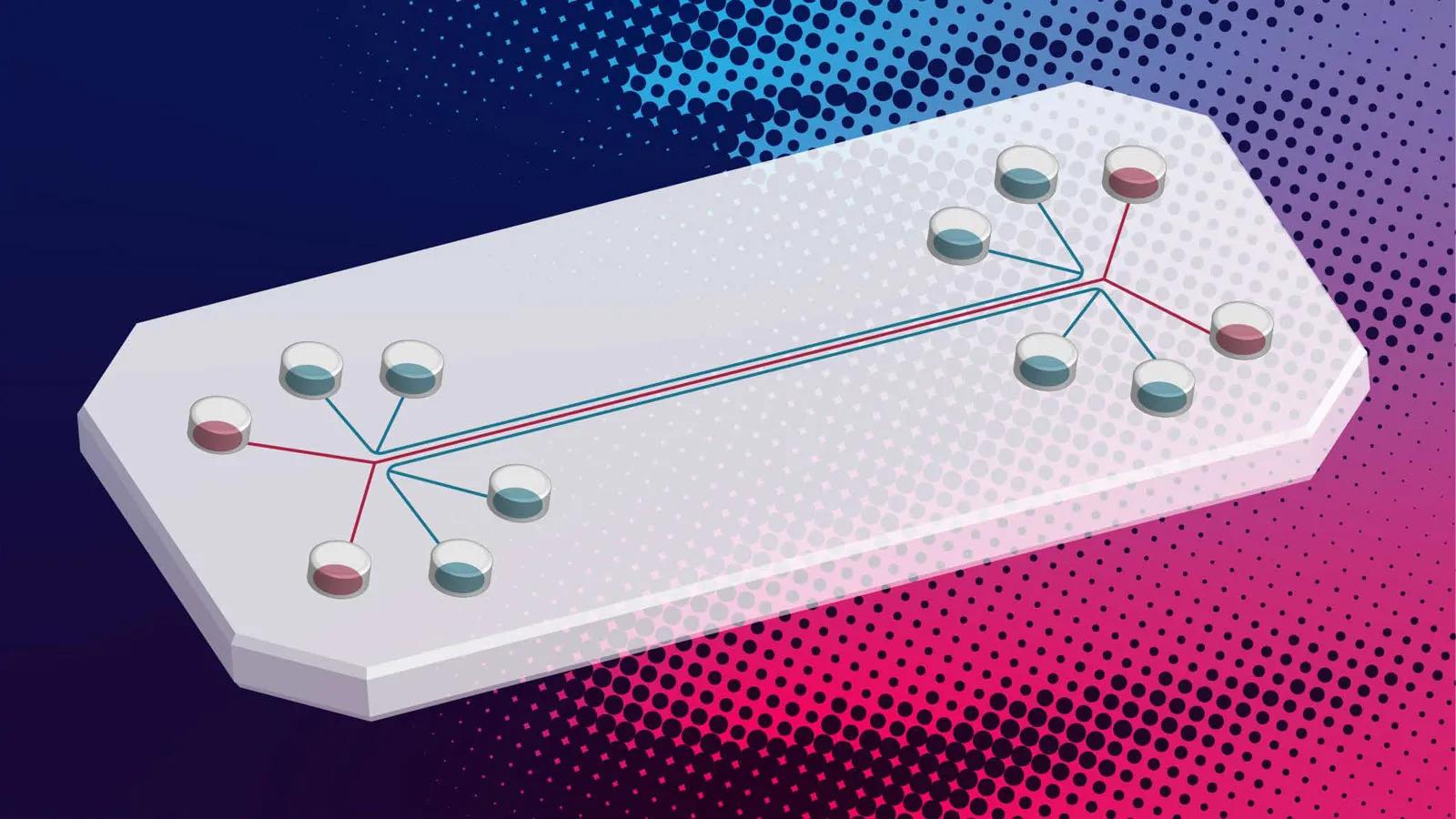

An organ-on-a-chip takes this a step further. Roughly the size of a USB stick, these clear plastic devices contain hollow microchannels that are lined with living human cells. Fluids continuously flow through them, creating conditions that mimic blood circulation, breathing motions, or even the physical stresses inside the gut. Unlike static petri dishes, these chips allow scientists to replicate the dynamic environment of the human body—where cells are never isolated, but always interacting with their neighbors cells, the microbiome, and the immune system.

“These platforms provide a much more dynamic environment compared to 2D culture systems, with flows similar to our bodily fluids,” said JAX Assistant Professor Sasan Jalili. “The physiological responses you get from 3D organoid and organ-on-chip systems are significantly more advanced and representative of human biology.”

“We can watch in real time how multiple cell types interact together or how the microbiome and immune system respond to perturbations, and that matters, because most traditional systems only give us static snapshots,” he added. “By capturing cellular dynamics as they unfold, we can follow disease processes in a way that much more closely mirrors what actually happens in patients.”

A window into disease and aging

Jalili’s lab is leveraging these advanced systems to investigate how the microbiome, immune system, and aging intersect to influence health and disease. By building skin and gut models from patient-derived cells, his team can directly compare how microbial shifts shape immune responses in younger versus older adults.

They’ve created a “gut-on-a-chip” platform, where intestinal epithelial cells form finger-like villi and secrete mucus, recreating key features of the intestinal barrier. When bacterial communities are introduced, they colonize the mucus layer. When immune cells are added to the vascular channel beneath, they actively migrate toward the bacteria during infection, mimicking the surveillance and defense mechanisms of the human gut. This dynamic setup allows scientists to observe host–microbe–immune interactions in real time, with a level of physiological fidelity far beyond traditional culture systems.

Toward better therapies

Why go to all this trouble? Because organoids and organs-on-chips bridge the gap between basic biology and human health. They capture the complexity of real tissues in ways animal models and traditional cell cultures cannot, offering more accurate predictions of how patients might respond to therapies.

A major focus of the Jalili lab is on colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). With colorectal cancer cases rising sharply in younger populations, the team is working to understand the mechanisms that drive early- and late-onset disease. In collaboration with Connecticut Children’s Hospital, they are developing patient-specific gut-on-chip models using matched biopsies, stool, and blood samples from pediatric patients. These personalized systems provide an opportunity to uncover triggers of IBD, trace the progression of colorectal cancer, and evaluate microbiome-targeted and immunomodulatory therapies aimed at preventing metastasis and improving patient outcomes.

Organoids and organs-on-chips create connections between basic biology and clinical application. They enable researchers to model human disease processes more accurately than conventional culture systems, while avoiding some of the limitations of animal models.

These technologies offer a path toward not only understanding disease mechanisms but also developing more precise diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for patients. For Jalili and colleagues, the long-term vision is clear: to use these living models not only to uncover the cellular and molecular mechanisms of autoimmune diseases, cancer, and aging, but also to pave the way for new diagnostics and innovative therapies, ultimately advancing personalized medicine approaches where the right treatment can be matched to the right patient at the right time.

Jalili, who is also an assistant professor at the UConn School of Medicine, was named a 2025 UConn Pepper Scholar. UConn’s Pepper Center champions advancements of aging research, Jalili's research project focus: “Investigating Local Immune-Microbiome Interactions in Skin from Frail Older Adults Using Sampling Microneedle Patches.”

Learn More

Sasan Jalili, Ph.D.

Sasan Jalili, Ph.D., explores microbiome-immune crosstalk and develops innovative therapeutic tools, including microneedle skin patches, organoid engineering, and organ-on-chip systems to advance immune-related disease research.

View more

Explore Cancer Research Tools and Technologies

Discover tools and technologies scientists are using to advance the field of cancer research, including next-generation sequencing, cell-based models of cancer, and mouse models of cancer in this self-paced JAX Online MiniCourse.