Thinking big

The Search Magazine Article | March 22, 2022

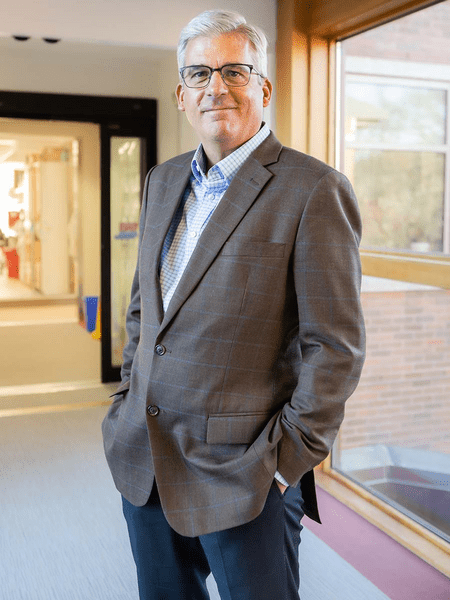

“JAX presents the opportunity for me to do what I’ve been dedicated to doing my entire career: to translate genetic discoveries into human health,” says Lon Cardon, Ph.D., FMedSci, who joined The Jackson Laboratory as president and CEO in November 2021.

“It’s time to ask not only what genes cause a disease,” he adds, “but can we work on those genes tocorrect the disease?”

Cardon is uniquely qualified to address that big question. An internationally renowned expert in human genetics, his career began in academic research at Oxford University and the University of Washington. He came to JAX from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., a rare-disease biotechnology company where he was chief scientific officer and chief scientific strategy officer. Previously, he was senior vice president and head of genetics, quantitative sciences and alternative discovery and development at GlaxoSmithKline plc, the U.K.-based multinational pharma giant.

Tim Dattels, vice chair of the JAX Board of Trustees, led the JAX presidential search committee formed in 2021 when Edison Liu , M.D., announced he would step down as president and CEO and remain on the research faculty.

It's time to ask not only what genes cause a disease, but can we work on those genes to correct the disease?

“The search committee identified a long list of qualities we were seeking,” Dattels says, “and we knew finding the right person would be a bit like searching for a unicorn. In Lon Cardon, we found not just a unicorn but a purple, spotted unicorn: a brilliant scientist with a passion for translating discoveries into human impact; depth and breadth of experience spanning academe, biotech and pharma; and the leadership and people skills to work effectively with colleagues across the Laboratory, the board, and JAX’s wide and varied network of collaborators and supporters.”

Cardon says, “My initial impressions of JAX have exceeded even my highest hopes. The research is simply outstanding and includes a surprisingly broad range of biology, technology and disease areas. In particular, research that spans the interface between mouse and man, which is clearly a sweet spot for JAX, is embraced so broadly here that it seems part of the JAX DNA. This is apparent throughout JAX® Mice, Clinical and Research Services, across the faculty, and deep in the support and scientific services areas.”

From student to mentor

Cardon conducted his Ph.D. research at the Institute for Behavioral Genetics at the University of Colorado Boulder, under the mentorship of the late David Fulker, who was himself an academic descendent of the genetics pioneer R.A. Fisher. “David had maybe five students, but he spent 90% of his time with me,” he recalls. “Why would he do that? I wasn’t very interesting! Maybe I worked harder than the others. But he was a lifelong friend.”

After postdoctoral training in the mathematics department of Stanford University, Cardon moved to England with his wife and new son for an academic post in Oxford University’s Medical Sciences Division. There, a Canadian-born immunologist and geneticist took him under his wing. Cardon’s Oxford mentor was Sir John Bell, Regius Professor of Medicine, a title that King Henry VIII originated in 1546 and that formally makes Bell the chief medical advisor to the Queen of England. “He really paved the way for me,” Cardon says. “Because of him, I was able to obtain the highest and most prestigious fellowship granted by The Wellcome Trust that led to a professorship in Oxford at an unusually young age.”

Asked about his former student, Bell responds, “Lon is one of the most impressive statistical geneticists who, over many years, has been able to bridge successfully the divide between academic excellence and commercial reality. He has achieved a great deal in both domains, and this has had an enormous impact on progress in the field. His time with us in Oxford was extraordinarily productive, and he even managed to find a little spare time to get a bit of skiing and sailing done!”

Cardon was a co-founder of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium at Oxford University, which yielded the first genome-wide association studies, a landmark approach to associating specific genetic variants with specific diseases. This project was among the many large international genetics initiatives in which Cardon has had a significant role, projects that helped to create the present global genomics research infrastructure. And Cardon became a mentor to a whole cadre of successful young scientists.

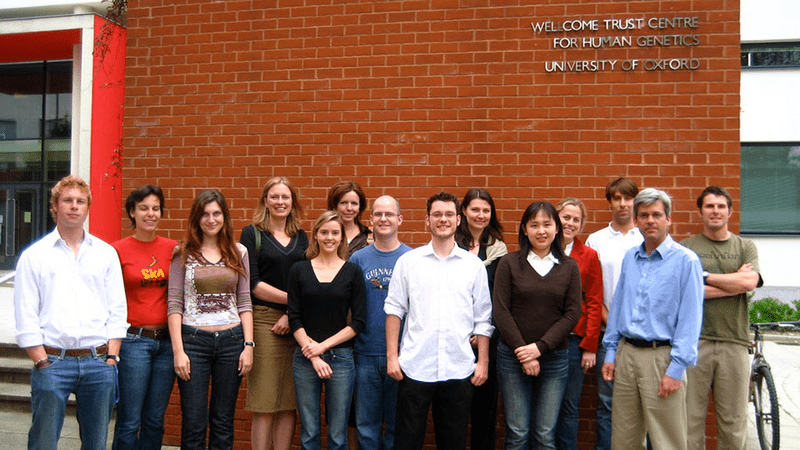

Jeffrey Barrett joined Cardon’s lab team at Oxford as a Ph.D. candidate in 2005 and is now the chief scientific officer of Nightingale Health, a health technology company based in Helsinki, Finland, focused on preventive care.

“It was an exciting time to be in genetics because a combination of new technology, the recent completion of the Human Genome Project and excellent clinical collaborators meant research projects were possible that really started to understand the genetic basis of common human diseases,” Barrett says.

This 2007 photo of Lon Cardon’s lab group at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics at the University of Oxford shows Cardon (front row, far right) and students that include four future professors, two future institute directors and the future chief scientific officer at Nightingale Health, Jeffrey Barrett (center, blue t-shirt). Photo courtesy Jeffrey Barrett.

This 2007 photo of Lon Cardon’s lab group at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics at the University of Oxford shows Cardon (front row, far right) and students that include four future professors, two future institute directors and the future chief scientific officer at Nightingale Health, Jeffrey Barrett (center, blue t-shirt). Photo courtesy Jeffrey Barrett.

Barrett says Cardon taught him “that the essence of leadership is setting people up to do their best work and giving them the freedom to pursue success. It’s something I’ve tried to emulate ever since in my career, and so I believe some of Lon’s generosity has been passed on to subsequent generations of scientists.”

Another one of Cardon’s Ph.D. students at Oxford was Gonçalo Abecasis, who is now vice president and chief genomics and data science officer at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., headquartered in Tarrytown, N.Y.

Abecasis says he learned two major lessons from Cardon. “One is to go big. Lon really liked the idea of going for big, transformational experiments. Instead of starting with a small dataset of 1,000 people, he would say, let’s get 60,000. In genetics that turns out to be a very good strategy, because the cost of genetic data keeps going down. There are always possibilities for scaling things up.”

Likewise, Abecasis says, “Lon taught me to squeeze the maximum out of an experiment. At Oxford we had good funding, but Lon would say, ‘Let’s not just spend the money; what’s really the best we can do?’ Where we had originally planned to use our budget to buy 10 computers, he challenged me to get 40 or 50, and I did a lot of calling around and haggling with suppliers. For a while we had a computer cluster at the back of his office, so it was always a little warm in there!”

The second key takeaway from Abecasis’ time in the Cardon lab was collaboration. “Lon used to talk about himself as a geek,” he comments, “and it’s true that he’s really, really good at the statistics and genetics. But he also always partners with people who are fantastic at other parts of the process, whether it’s medicine, drug development or new technologies. There are a lot of good things that can happen when you learn how to build those partnerships.”

From ‘electrician’ to scientist

Cardon was born in Bremerton, Wash. When it came to developing a work ethic early in life, Cardon says, “My mother was probably my model. She and my father divorced when I was about 11, and for about four years she was raising four kids on her own while working her way through college to become a nurse. We were latchkey kids who had to learn to be independent, and we didn't have much. Things got better when she married our stepdad, a fireman, but I think we all followed the example she set.”

As a kid, Cardon describes himself as more electrician than budding scientist. “I had all the little sets that let you wire things together and create batteries, that kind of thing.” That tinkering inclination has stayed with Cardon. “I still love taking things apart to see how they work,” he says, “though my wife will tell you I’m not too adept at putting them back together.”

Though good at math throughout elementary and high school, Cardon didn’t think of himself as a scientist until he enrolled at the University of Puget Sound as an undergraduate. “And what I discovered is,” Cardon says, “not that I was naturally good at science or anything else, but I was good at asking critical questions. In fact, that's what I teach young people today: You don't have to be the best scientist in the room, but if you can ask good questions about something that's not in your field, you can be successful.”

At college, Cardon discovered he liked biology and took a pre-med major. “There was a math-statistics track and then there was medicine. At the time we didn’t have data sciences, or a way to combine math and biology, and I decided that’s what I really wanted to do.”

In person Cardon exudes a rare combination of energy and fidget-free focus, qualities that come in handy as a scientist and leader, but also in his “unleisurely” downtime pursuits — downhill skiing and sailing.

“I don’t shut down particularly well,” Cardon says, “but I recognize how much better I can perform when I manage to do it, so I try hard to find balance outside of work. Sailing and cycling in the summer focus my mind on other things (especially in San Francisco where there is a lot of wind to keep my mind in survival mode when sailing, and a lot of traffic to help me think of staying upright on my bike). In the winter I love skiing with my family.” He says he doesn’t watch much TV and so is a “horrible conversationalist” about entertainment, but enjoys catching up on scientific journals and listening to music.