The severe combined immunodeficiency scid mutation

JAX Notes | April 1, 1993History of the scid mutation

Four littermates of the C.B-17 inbred strain (BALB/c.C57BL/Ka-Igh-1b/Icr N17F34) were initially found to lack detectable IgM, IgG1, and IgG2a during a serum immunoglobulin quantitation study. This defect was demonstrated to be a heritable trait under the control of a recessive mutation (Bosma, et al., 1983). The mice were determined to lack both T and B cells, resulting in a disease similar to severe combined immunodeficiency as reported in humans (Giblett, et al., 1972; Hirshhorn, et al., 1979; McKusick, 1990) and Arabian foals (McGuire, et al., 1974). The mutant locus, designatedscid for severe combined immunodeficiency, was mapped to mouse chromosome 16 (Bosma, et al., 1989).

Gross lesions

Lymphoid organs in homozygous scid/scid mice are small or extremely difficult to find at the time of necropsy. Heterozygous scid/+ mice have lymphoid organs of normal size. Although many other mouse mutations with immunodeficiencies have skin and hair abnormalities, thescid/scid mice have normal pelage and skin. Homozygotes (scid/scid) maintained in barriers with sterilized food and water, and have no other gross lesions.

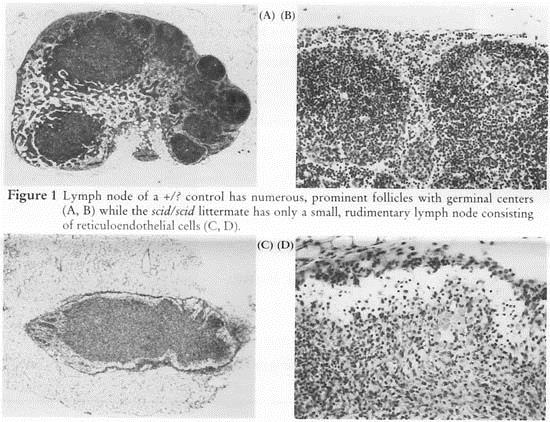

Figure 1 Lymph node of a +/? control has numerous, prominent follicles with germinal centers (A,B) while the scid/scid littermate has only a small, rudimentary lymph node consisting of reticuloendothelial cells (C, D). Microscopic lesions

Figure 1 Lymph node of a +/? control has numerous, prominent follicles with germinal centers (A,B) while thescid/scid littermate has only a small, rudimentary lymph node consisting of reticuloendothelial cells (C, D).

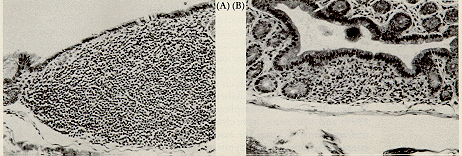

There is a generalized lymphopenia, rudimentary thymic medulla without a cortex, lymph nodes without follicles (Fig. 1) and a small spleen lacking white pulp. Lymphoid aggregates in the lung and gastrointestinal tract are rudimentary, consisting of reticuloendothelial cells (Fig. 2; Custer, et al., 1985).

Immunologic and biochemical lesions

Severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mice have been found to lack functional T and B cells as well as Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells, but they exhibit normal differentiation and function of myeloid cells, antigen presenting cells, and natural killer cells (Nixon-Fulton, et al., 1987; Shultz, 1991; Dorshkind, et al., 1984; 1985; Czitrom, et al., 1985). This mutation appears to cause an abnormal recombinase system for the assemblage of antigen receptor genes in developing lymphocytes (Review:Shultz, 1991).

The defect appears to be restricted to the level of the lymphopoietic stem cell. While the majority ofscid/scid mice lack functional lymphoid cells, approximately 15% of scid/scid mice express detectable serum Ig. These so called "leaky" scid/scid mice also express functional T cells (Bosma, et al., 1988).

Figure 2. The gut associated lymphoid tissue is prominent in colon of the +/? control (A) while it is almost nonexistent in the scid/scid littermate (B). Background lesions

Thymic T-cell lymphomas occur in approximately 15% of aged C.B17/Icr-scid/scid mice (Custer, et al., 1985). The frequency increases to 67% in 40-week-old NOD-scid/scid mice (Prochazka, et al., 1992). The NOD-scid/scid mouse has been suggested as a model for spontaneous thymomagenesis associated with immunodeficiency. It has been proposed that the unusual features of T-cell ontogeny, characteristic of the NOD inbred strains, is synergistic with the scid-imparted block in thymocyte development, leading to activation of the unique NOD ecotropic provirus,Emv-30 (Prochazka, et al., 1992).

The severe immunodeficiency in scid/scid mice results in increased susceptibility to opportunistic microorganisms, requiring specific pathogen-free facilities for their maintenance. Even still, unless strict barriers are maintained for caesarian-derived mice, Pneumocystis carinii infection often occurs (Shultz, et al., 1989; Sundberg, et al., 1989).

The nature of noninfectious diseases that occur in scid/scid mice depends on their inbred genetic background. For example, epicardial mineralization has been reported in clinically normal scid/scid mice on the C.B-17/Icr inbred background (Meador, et al., 1992). Heterozygous mice were not used as controls. This lesion is common in various BALB/c inbred strains, from which the C.B-17 was derived. Epicardial mineralization is an inbred strain characteristic, since such cardiac mineralization has not been observed in all congenic strains carrying the scid mutation (Sundberg, unpublished data).

Homologous human disease

Severe combined immunodeficiency occurs in humans as an autosomal recessive trait (Hirschhorn, et al., 1979; McKusick, 1990) or X-linked characteristic (McKusick, 1990) that is clinically very similar to the mousescid mutation. Schwartz, et al. (1991) described five human patients with impaired rearrangement processes at the JH region analogous to the defect in scid/scid mice. The deficiency may also be associated with a deficiency of adenosine deaminase (Hirschhorn, et al., 1979; Giblet, et al., 1972). As with scid/scid mice, if human patients are not protected from environmental pathogens, they will die as a result of bacterial, viral and/or mycotic infections (Hoyer, et al., 1968).

Homologous animal disease

A clinically similar severe combined immunodeficiency disease occurs in Arabian foals (McGuire, et al., 1974). This equine disease has been shown to be due to an autosomal recessive mutation (Perryman and Torbeck, 1980). Adenosine deaminase and purine nucleoside phosphorylase activities are within normal limits (McGuire, et al., 1976) although purine metabolic abnormalities have been detected and deoxyadenosine metabolism is altered in severe combined immunodeficient foals (review: Perryman, et al., 1983).

Common uses of the severe combined immunodeficiency mutation

Although the scid mouse mutation is useful as an animal model for the human disease of the same name, it is more valuable as a biomedical tool to investigate fundamental biological processes. The NOD-scid/scid appears to be a useful model for investigating mechanisms of spontaneous thymomagenesis associated with immunodeficiency (Prochazka, et al., 1992). NOD (non-obese diabetic) mice spontaneously develop T-lymphocyte mediated autoimmune insulitis and diabetes mellitus (type 1). The NOD-scid/scid mouse, which is both insulitis-and diabetes-free, serves as an ideal recipient for adoptive transfer of diabetes by purified T cell subsets (Christianson, et al., in press). Successful reports of transplantation of human neoplasms (Reddy et al., 1987; Phillips, et al., 1989) and xenogenic hybridoma cells (Ware, et al., 1985) has led to the extensive use of scid/scid mice as hosts for normal and malignant tissue transplants.

Renal capsular grafts containing human fetal thymic tissue followed by injection of fetal liver cells intoscid/scid mice resulted in the so-called SCID-hu mouse, which expressed lymphoid cells of human origin (McCune, et al., 1989). The heterochimeric SCID-hu mice have been successfully infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), making them a potentially valuable model for the testing of new drugs for AIDS treatment (Namikawa, et al., 1988). Pneumocystis carinii infection is common in some colonies of scid mice, making them useful as models for studying the pathogenesis and treatment of this infectious disease (Shultz, et al., 1989; Sundberg, et al., 1989). Other infectious diseases and parasites that would not naturally or experimentally infect immunocompetent animals, such as Onchocerca volvulus and Brugia malayi (Nelson, et al., 1991; Rajan, et al., 1992), have been propagated in scid/scid mice, opening up potential uses for this mouse mutation.

Other mouse mutations have underlying hematopoeitic stem cell defects that cause the abnormal phenotype. Thescid mouse can serve as a bone marrow recipient to test this hypothesis (Sundberg, et al., 1993). The role of various aspects of the immune system on the pathogenesis of mouse mutations can be assessed by intercrossing the mutation being studied with the scid mutation, creating double homozygous mutants (Sundberg, et al., 1993; Shultz, 1991b; Leiter, et al., 1987).

Availability of mice

Severe combined immunodeficiency mutant mice are available on a number of congenic backgrounds including C3H/HeJ, C57BL/6J, and BALB/cByJ. Before requesting these mice, call the Customer Service Department at 1-800-422-MICE for information on availability and health status.

References

1. Bosma, GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. A severe combined immunodeficiency mutant in the mouse. Nature 301:527-530, 1983.

2. Bosma GC, Davisson MT, Ruetsch NR, Sweet HO, Shultz LD, Bosma MJ. The mouse mutation severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) is on chromosome 16. Immunogenetics 29:54-56, 1989.

3. Bosma GC, Fried M, Custer RP, Carroll A, Gilson DM, Bosma MJ. Evidence of finding lymphocytes in some (leaky) SCID mice. J exp Med 167:1016-1033, 1988.

4. Christianson SW, Shultz LD, Leiter EH. Adoptive transfer of diabetes into immunodeficient NOD-scid/scid mice: relative contributions of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes from diabetic versus prediabetic NOD.NON-Thy-1a donors. Diabetes. in press.

5. Custer RP, Bosma GC, Bosma MJ. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in the mouse. Am J Pathol 120:464 477, 1985.

6. Czitrom AA, Edwards S, Phillips RA, Bosma MJ, Marrack P, Kappler JW. The function of antigen-presenting cells in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. J Immunol 134:2276-2280, 1985.

7. Dorschkind K. The severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse. Immunologic Disorders in Mice. Edited by B Rihova, V Vetvicka, Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, 1991, pp 1-21.

8. Dorshkind K, Pollack SB, Bosma MJ, Phillips RA. Natural killer (NK) cells are present in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). J Immunol 134:3798-3801, 1985.

9. Giblett ER, Anderson JE, Cohen F, Pollara B, Meuwissen HJ. Adenosine deaminase deficiency in two patients with severely impaired cellular immunity. Lancet 2:1067-1069, 1972.

10. Hirschhorn R, Vawter GF, Kirkpatrick JA, Rosen FS. Adenosine deaminase deficiency: frequency and comparative pathology in autosomally recessive severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol immunopathol 14:107-120, 1979.

11. Leiter EH, Prochazcha M, Shultz LD. Effect of immunodeficiency on diabetogenesis in genetically diabetic (db/db) mice. J Immunol 138:3224-3229, 1987.

12. McCune JM, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Shultz LD, Lieberman M, Weissman IL. The SCID-hu mouse: murine model for the analysis of human hematolymphoid differentiation and function. Science 241:1632-1639, 1988.

13. McGuire TC, Poppie MJ, Banks KL. Combined (B- and T-lymphocyte) immunodeficiency: A fatal disease in Arabian foals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 164:70-76, 1974.

14. McKusick VA. Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Catalogs of Autosomal Dominant, Autosomal Recessive, and X-Linked Phenotypes. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1990, pp. 20-26, 1015.

15. Meador VP, Tyler RD, Plunkett ML. Epicardial and corneal mineralization in clinically normal severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice. Vet Pathol 29:247-249, 1992.

16. Nanikawa R, Kaneshima H, Lieberman M, Weissman IL, McCune JM. Infection of the SCID-hu mouse by HIV-1. Science 242:1684-1686, 1988.

17. Nelson FK, Greiner DL, Shultz LD, Rajan TV. The immunodeficient scid mouse as a model for human lymphatic filariasis. J Exp Med 173:659-663, 1991.

18. Nixon-Fulton JL, Witte PL, Tigelaar RC, Bergstresser PR, Kumar V. Lack of dendritic Thy-1+ epidermal cells in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency disease. J Immunol 138:2902-2905, 1987.

19. Phillips RA, Jewett MAS, Gallie BL. Growth of human tumors in immune deficientscid mice and nude mice. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 152:259-263, 1989.

20. Perryman LE, McGuire TC, Magnuson NS. Combined immunodeficiency (severe), Swiss-type agammaglobulinemia, Model No. 83, supplemental update, 1983. In:Handbook: Animal Models of Human Disease. Fasc. 12, Capen DD, Hackel DB, Jones TC, Migaki G, eds., Reg Comp Pathol, AFIP, Washington, D.C. 1983 pp. 1-4.

21. Perryman LE, Torbeck RL. Combined immunodeficiency of Arabian horses: Confirmation of an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. J Am Vet Med Assoc 176:1250-1251, 1980.

22. Prochazka FM, Gaskins HR, Shultz LD, Leiter EH. The nonobese diabeticscid mouse: Model for spontaneous thymomagenesis associated with immunodeficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:3290-3294, 1992.

23. Rajan TV, Nelson FK, Cupp E, Shultz LD, Greiner DL. Survival of Oncocerca volvulus in nodules implanted in immunodeficient rodents. J Parasitol 78:160-163, 1992.

24. Reedy S, Piccione D, Takita H, Bankert RB. Human lung tumor growth established in the lung and subcutaneous tissue of mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Cancer Res 47:2456-2460, 1987.

25. Schwartz K, Hansen-Hagge TE, Knobloch C, Friedrich W, Kleihauer E, Bartram CR. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in man: B cell-negative (B-) SCID patients exhibit an irregular recombination pattern at the JH locus. J Exp Med 174:1039-1048, 1991.

26. Shultz LD. Immunological mutants of the mouse. Am J Anat 191:303-311, 1991a.

27. Shultz LD. Hematopoiesis and models of immunodeficiency. Sem Immunol 3:397-408, 1991b.

28. Shultz LD. Schweitzer P, Hall EJ, Sundberg JP, Taylor S, Walzer PD.Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in scid/scid mice. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol 152:243-249, 1989.

29. Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, Beamer WG, Shultz LD. Role of hematopoietic progenitor cells in development of psoriasiform dermatitis in the flaky skin mutant mouse. Immunol Invest in press.

30. Sundberg JP, Burnstein T, Shultz LD. Bedigian H. Identification ofPneumocystis carinii in immunodeficient mice. Lab Anim Sci 39:213-218, 1989.

31. Ware CF, Donato NJ, Dorschkind K. Human, rat or mouse hybridomas secrete high levels of monoclonal antibodies following transplantation into mice with severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID). J Immunol Methods 85:353-361, 1985.