One of the most pressing areas in modern scientific research is the cause, treatment, and prevention of cancer.

A major breakthrough in cancer treatment was the development of chemotherapy in the 1940s. Chemotherapy refers to the use of chemical agents to kill cancer cells, most commonly by causing defects in the cell cycle, making it more difficult for cancer cells to proliferate and spread. The first chemical noted for its anti-cancer effects were nitrogen mustards, similar to the sulfur mustard gas compounds developed for chemical warfare during World War I.

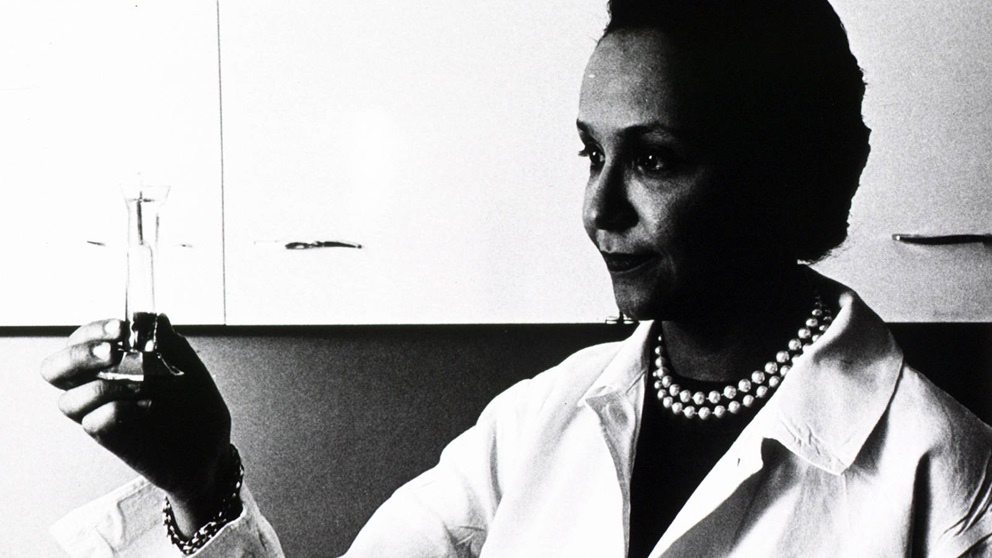

Soon after, scientists across the country were researching other compounds with possible anti-tumorigenic function in humans. Dr. Jane Cooke Wright played a fundamental role in this story. During her career she would break multiple race and gender barriers and become one of the most distinguished physician-scientists in modern medicine.

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright was born on Nov. 20, 1919, to Dr. Louis T. Wright and Corinne Cooke. The Wright family had a strong history of academic achievement in medicine. Her paternal grandfather Dr. Ceah Ketcham Wright was born into slavery, and after the Civil War earned his M.D. at Meharry Medical College. Her step-grandfather was Dr. William Fletcher Penn, the first African American to graduate from Yale Medical College. And Jane’s father, Dr. Louis T. Wright, was among the first black students to earn an M.D. from Harvard Medical school as well as the first African-American doctor appointed to a public hospital in New York City. He went on to found the Cancer Research Center at Harlem Hospital in New York City in 1947, and was a renowned cancer scientist and surgeon. Both Jane and her sister would also become physicians, championing a field largely dominated by white men.

Dr. Jane Wright attended Smith College originally wanting to pursue a degree in art. At the suggestion of her father she changed to pre-med studies, and earned a full scholarship to study medicine at New York Medical College. She was voted vice president of her class and graduated with honors in 1945, as part of an accelerated three-year program. Dr. Wright interned at Bellevue Hospital and completed her surgical residency at Harlem hospital in 1948.

In 1949 Dr. Wright joined her father at the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem hospital, where they began research on potential chemotherapeutic agents. In the 1940s chemotherapy was considered a “last resort” treatment option and was still in the experimental stages of drug development. As a result, the types of chemotherapy drugs available and their prescribed dosages were not well defined. The Wrights were one of the first groups to report the use of nitrogen-mustard agents as a treatment for cancer, which led to remissions in patients with sarcoma, Hodgkin’s disease, chronic myelogenous leukemia, and lymphoma. Prior to these treatments many blood cancers were seen as incurable. In later articles Dr. Wright would refer to chemotherapy as the “Cinderella of cancer research,” for it’s incredible potential in treating multiple types of lethal cancers.

The Wrights were also some of the first researchers to test folic acid antagonists as cancer treatments. Folic acid antagonists block the function of folic acid in the body. Folic acid is required for cells to produce certain types of amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins, and purines, one of the main components of DNA and RNA. (This is why pregnant women take folic acid supplements- they are supporting a ton of cell division!) By inhibiting folic acid, cells cannot make new strands of DNA/RNA or produce proteins to drive cell processes. Eventually, unable to repair the massive amount of cell damage, these cell die. Cancer cells are highly proliferative compared to the majority of cells in the human body. So, although treatment with antifolates affects both tumor cells and non-tumor cells, it has more of an effect on these highly active tumor cells.

Among all the drugs they tested, the folic acid antagonists were probably the most important. In a 1951 paper they reported for the first time that antifolates are highly potent against a vast array of solid tumors, including several types of leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, lymphosarcoma, melanoma, breast cancer, and prostate cancer. Of the 93 patients they treated, 24 cases showed measurable improvements, such as reducing swelling of lymph nodes, increased mobility of paralyzed joints, and improved blood cell counts. The most successful folic acid antagonist they tested was methotrexate; of the 28 patients receiving methotrexate, 10 displayed objective improvements. This was a truly ground breaking paper, as they tested the long-term efficacy of combination therapy as well, and tested the idea of adjusting doses and length of therapy based on symptoms of toxicity associated with the chemotherapy drugs. Methotrexate is still one of the main chemotherapy drugs used today to treat breast cancer, leukemia, lung cancer, osteosarcoma, and many other types of cancer. This discovery truly formed the basis for all modern chemotherapy research.

In 1952, following her father’s death, Dr. Jane Wright was appointed the director of the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem Hospital. In 1955 she became an associate professor of surgical research and director of cancer chemotherapy research at New York University Medical Center, and she turned her research program towards personalized medicine. Wright pioneered efforts in utilizing patient tumor biopsies for drug testing, to help select drugs that may work specifically against a particular tumor. In these experiments, a small piece of the tumor was excised surgically and cultured in the laboratory. Once these cells were coaxed to grow, an arduous process in the 1950s, tumor cells were treated with different drugs in culture to help predict which drugs may produce the most robust effect in the actual patient. This is another revolutionary idea from Dr. Wright, which underlies the contemporary concept of precision medicine.

The potential for patient-specific cell culture in chemotherapy and cancer drug research was the overwhelming motive of Wright’s career. As a result, her efforts were also seen in cancer treatment methods, where she developed a nonsurgical procedure using a catheter to deliver toxic chemotherapy drugs to tumors in previously inaccessible areas, such as the kidneys and spleen.

Dr. Wright’s work was so well known and respected that, in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed her to the President's Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke. She also served on the National Cancer Advisory Board from 1966-1970. These boards stressed that improved communication was needed among the various hospitals and research institutes across the United States to raise the standard of clinical care for all Americans. The Commission was successful in establishing a network of Regional Medical Programs (RMP), which supported cooperative arrangements among medical schools, research institutions, and hospitals to implement the latest and most advanced clinical treatments nationwide.

This problem, of ensuring access to quality medical care across the country, is still a problem today. Dr. Wright wanted to make sure that her research was helping everyone, because she knew it was that important and life-saving. Many other cancer researchers felt the same. She met with six other oncologists in April 1964 to found the American Society of Clinical Oncology, whose goal is to help educate doctors and provide training, educational, and clinical research grants. It is worth noting that she was the only African American and woman at the meeting that day. At this point, Dr. Wright was probably accustomed to these gender and race dynamics, as they were barriers she would cross several times during her career.

She accomplished all of this before the Civil Rights Act was passed in June of 1964, which outlawed discrimination based on sex, race, and religion. Her father had been a champion of the Civil Rights Movement in New York, advocating for integration of hospitals and equal employment opportunities for black doctors and nurses. The Wright family had a legacy of fighting for the rights of patients, and Jane was no exception.

Dr. Wright continued her research on chemotherapy and tissue culture, publishing over 100 articles during her career. In 1967 she was named Professor of Surgery, Head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department, and Associate Dean at the New York Medical College. She was the highest-ranking black woman among all American medical institutes at this time. And in 1971, she became the first female President of the New York Cancer Society.

She did not often comment on her race or gender, but I found the following quote from a The New York Post 1967 interview interesting. “I know I’m a member of two minority groups, but I don’t think of myself that way. Sure, a woman has to try twice as hard. But — racial prejudice? I’ve met very little of it.” She then added, “It could be I met it — and wasn’t intelligent enough to recognize it.” I would argue that, instead, she was too busy being brilliant to give credence to opinions or beliefs that would stand in her way.

Dr. Jane C. Wright was one of the leading physician-scientists of her time, screening hundreds of drugs for their potential to kill human tumors and studying how these drugs could be tested in cell culture. The sum of her work revolutionized cancer research and how physicians treat cancer. She also cared a great deal for her patients, and supported standardized medical care across the United States and internationally. Her tireless efforts can still be witnessed today in the many medical societies and patient advocacy groups she served, as well as the continued work to regulate medical care and improve patient outcomes. Dr. Wright was one of those rare individuals whose compassion and intelligence worked together to truly leave the world a better place.

Ellen Elliott, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral fellow at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine in Farmington, Conn. Ellen works in the laboratory of Adam Williams, Ph.D., where she is studying the function of long non-coding RNAs in TH2 cells and asthma. Follow Ellen on Twitter at @EllenNichole.

Ellen Elliott, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral fellow at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine in Farmington, Conn. Ellen works in the laboratory of Adam Williams, Ph.D., where she is studying the function of long non-coding RNAs in TH2 cells and asthma. Follow Ellen on Twitter at @EllenNichole.